Browntown’s Black Population 1872 to 1901

The 1840 census for Warren County reported that the county’s population was 5,627, of whom 1,434 (25.5%) were enslaved. In 1860 25% of the population of the county were black, most of them enslaved. For a variety of reasons Front Royal and towns like it in the Shenandoah Valley, also attracted emancipated free blacks during this period but we have no information on the numbers involved.

The Civil War changed everything, with most young or middle-aged white men leaving to fight for the Confederacy and wives, grandparents, young children, and slaves left to manage their farms as best they could.

After the civil war ended in 1865 things were slow to change in the Gooney Valley. With slavery abolished and rights restored, some blacks would have moved quickly to establish their independence while others faced many difficulties with their new found freedom, as illustrated in this description of the experience of a black family who ended up in Browntown:

“One black Warren County resident remembers an older relative telling her “Our master called us all in and told us we were free, he said he couldn’t afford to take care of us anymore”. They had never been off the farm. They were given some supplies and they took off walking. They slept in the fields and “ate the things that were good to eat.” They ended up in Browntown. The husband would go out into the woods and find bark to sell to the tannery in order to live and survive”

(Source: Freedom Road: Warren County’s Black History, 1836-1988, by Betty Kilby Fisher)

In 1872, the Cover brothers opened a tannery in Browntown and hired a sizeable black labor force, beginning a transformation of Browntown into an industrialized village that would grow and develop for the next forty years or so. In August, 1879 the Warren Sentinel described the beginnings of this transformation:

“The village seven years ago would hardly have deserved that name, for it could only boast of three or four houses, a blacksmith shop and, in apple time, a brandy camp. The Browntown of today, however, is in fact a prosperous village; thirty or forty tasty dwellings now adorn the place with a population of from two hundred to two hundred and fifty… All seem willing to accord this progressive spirit to the Cover Bros. These gentlemen have erected within the corporation limits a large steam tannery furnishing employment regularly to fifteen or twenty hands, besides distributing annually thousands of dollars to the bark peelers of the neighborhood.”

The impact of the Cover Brothers Tannery, using oak and chestnut bark from the surrounding mountains, included support jobs for timbermen who cut the trees, peelers to take the bark from them, and teamsters to haul timber, bark, and the finished product. The tannery also stimulated the opening of other businesses with associated employment opportunities in Browntown, including carpentry and building operations, a woolen factory, a wagon-maker shop, a hotel, a hardwood factory, a cooper shop for making barrels, and a legal distillery.

Many of those employed in these businesses would have been free blacks and formerly enslaved men (and some women). They would have brought their families with them and lived mainly in accommodation provided by their employers or in small shacks erected, most likely in the area immediately northwest of Browntown village.

Some also bought properties, e.g. we know that a large landowner, James W. (Willie) Boyd, in the 1870s began selling lots of an acre, a half-acre, or a quarter of an acre on either side of Gooney Run to both black and white residents. Rebecca Poe notes that “John Thornton ‘colored’” purchased one of these one-acre lots in 1877.

The “Lost” Colored Church and School

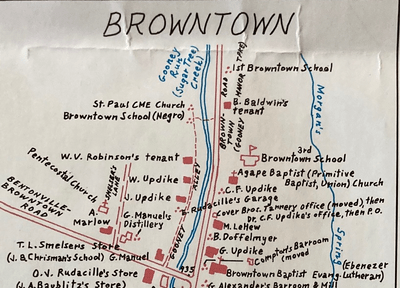

Our curiosity was aroused when in 2022 we acquired a copy of the highly detailed illustrated map of Warren County produced by the famed local historian Eugene Scheel.

The map shows the location of a “ruin” located on the west side of Gooney Run, just north of the BCCA. The ruin is labeled on the map as “Browntown School (Negro)”. To its immediate north is another ruin labeled “St. Paul CME Church”.

Subsequently we talked with a lot of people currently living in Browntown and learned that no one seemed to have heard of either this Negro school or the CME church. We then started to search online to see whether local newspapers from the late 1800s and early 1900s might shed any light on the history of these two forgotten institutions.

The St. Paul CME (Colored Methodist Episcopal) Church

In our online search we came across concrete evidence in an article in the March 1882 edition of the Warren Sentinel that a “colored” church did indeed exist in Browntown in the 1880s and that services were taking place as early as 1882. The Sentinel article, under the heading “Browntown Notes” states that:

“The colored brethren are enjoying a season of religious worship in their church here and we hope their efforts may not prove unavailing in bringing into the path of righteousness many that are out in the broad road of sin and folly.”

Most of the various histories of Browntown and its churches written since 1882 do not mention this colored church. It’s as if it never existed. The one exception is the work of local historian, Rebecca Poe, who states (exact source unknown) that “In 1878 John Thomas, David Mitchell, and Edward Curtis, trustees for the colored population of the Methodist church of Browntown, purchased a quarter-acre lot for a church.“

In The Gooney Bulletin, June, 1980, Poe indicates that both the Negro school and church were located “down the Creek side”, i.e. at the north end of Gooney Alley.

The only other information we have about this church comes from a website called Local Heritage Trail https://criserhigh.myevent.com) created by Robert King. Drawing on a 1963 thesis “Negro Education In Warren County” by James Mclendon, Mr. King says that the Mount Carmel Baptist Church on Indian Hollow Road in Bentonville was initially created in Browntown as St. Pauls Methodist church for African American worshippers. Other sources suggest that the Cover Brothers may have helped build the church for the families of black workers employed in their tannery.

The Browntown Colored School

The Browntown Colored Schoolhouse probably looked similar to the building in this photo of the colored schoolhouse in Ashburn, VA., built in 1892.

As was the case with the Colored CME Church, there are very few mentions of this school in published histories of Browntown.

During the Civil War and for at least the following five years the primary school system in Warren County was closed. Presumably, self-help efforts were made to provide some kind of schooling for children but there is no record of this.

According to James Mclendon’s thesis, the Browntown Colored School was one of the first schools established in Virginia to offer formal education to free and formerly enslaved blacks, in line with the 1870 Underwood Constitution that required Virginia to establish free public schools. Mclendon says that it took 13 years for these requirements to be implemented in Warren County.

Warren County eventually opened eight “colored” schools. The very first of these to open (in 1886) was in Browntown, which by the 1880s had a large percentage of African-American residents. Its founders and first teachers were Nathaniel N. Baker and his wife Maria. This same Nathaniel Taylor would later become the Principal of the progressive District 1 (“Freetown”) Colored School in Front Royal until his retirement in the 1920s.

After an encouraging start, the school appears to have had a checkered history. The first time the school is mentioned in the School Column of the Warren Sentinel is in October, 1900 when the County Superintendent, G.E. Roy, reported that he hoped the current “factions and divisions” among the colored patrons at Browntown and Limeton would cease and declared that “division among patrons of any school will destroy its efficiency and success. Let unity, harmony and well-wishing characterize all the schools.”

After an inspection visit two months later, the superintendent stated that he found the Browntown colored school “smaIl but well taught.” However, things clearly were not going well as he also reported that “Russell, the teacher, says some of his patrons, or who ought to be patrons, are opposed to him—he knows not why. There is a disposition to boycott Russell by some of the colored patrons, through division and prejudice. I am sorry about this.”

In April 1901, G.E. Roy was happy to find that the Limeton colored school had “improved very much. However, he was less happy about the Browntown colored school where “attendance has been smaller than it ought to have been.” By March, 1903, things came to a head and the Browntown colored school was closed. As far as is known, it never re-opened. The reason given for closing the school was “want of scholars.”

Doing something to address the issues that had led parents to boycott the school does not seem to have been a priority for the school authorities. The superintendent’s report simply states “I do not know what is the matter – I learn indirectly that factions and jealousies between the two colored churches at Browntown is partly the cause. The trustees should refuse another year to furnish a teacher, unless the colored people at that place would give some guarantee they would patronize it.”

(Note: the second colored church that G.E. refers to in this report would presumably have been the Union Church that was built in 1882 on the east side of Gooney Run. At least one of the denominations using this church on a once-a-month basis allowed whites and blacks to worship together, although the blacks were only allowed to sit in the balcony).

We have been unable to find out anything more about what educational provision was made for black children living in the Browntown area in the years immediately after the school closed.

The closure of the Cover Brothers Tannery in 1901 led to a major exodus of blacks from the Browntown community, with some moving to Pine Hills (Bentonville), Freetown (Front Royal) and surrounding enclaves.

Update to this article (October 3, 2024)

After doing the initial research for this article we were resigned to never knowing much more about what happened to the Browntown Colored School after its closure in 1903. However, our pessimism proved to be ill-founded when we came across an article in the April 6, 1932 edition of the Front Royal Record (a paper that only existed from 1920 to 1932). This article confirmed that the building itself was still standing in 1932 and being used as housing by a destitute family.

The article, authored by a well-known local journalist/celebrity, Charles W. Carson (who called himself “The Register Man”), begins with this plea from a subscriber to the newspaper:

“Dear Sir, as you seem to be the only one who is to be interested in relief work in Warren County, I wish to call your attention to a family of eight, living in a one room house on North Water Street, Browntown. This house was formerly the old colored schoolhouse. You cannot miss the place, as it is the first house on the right as you come into the hamlet. This family is in very destitute circumstances – they are in need of food, clothing, fuel, the barber, and also medical attention as the mother is now pregnant. The head of this family is a good worker, but has been unable to get work for some time, and consequently is starving in a land of plenty. This matter needs immediate attention.”

Charles Carson was clearly disturbed to learn about this family’s situation and consequently contacted the County Nurse, Miss Jeter, who confirmed that “she has this family on her list” and that the case would be taken care of as soon as possible. We have no way of knowing whether this family was black or white. Times were hard for many people in Warren County in the early 1930s, given the lack of jobs as a result of the Great Depression.

The fact that the school building was still in use in 1932 makes us hopeful that there may be more information or even photos still out there that will help us to understand what happened later to the schoolhouse and to the family living there in the 1930s.

NOTE: In addition to helping us learn more about the colored schoolhouse, this 1932 article also revealed another long-lost memory about the center of Browntown village: namely, that what we now call “Gooney Alley” was once known as “Water Street”.

The Current Site/Ruins of the Browntown Colored School and Church

Only a very exploratory visit has been made to these ruins, located at the north end of Gooney Alley. In 2023 we found the foundations of a 1-room building but, without a more thorough search there is no way of determining whether this building was the church or the school.

Part of the foundation of a building can be seen in the bottom half of this photo. The photo was taken on the west side of Gooney Run, at the north end of Gooney Alley, parallel with the north fence of the BCCA. The view is toward the south-east.

The steeple of the Union Church is just visible through the trees in the center of the photo.